Introduction: The Pulse of the Economy

The unemployment rate stands as one of the most scrutinized, cited, and consequential economic indicators in the modern world. It is far more than a simple percentage point announced monthly by government statistical agencies; it is a multifaceted pulse check on the economic and social health of a nation. This single figure influences central bank policy, sways stock markets, shapes political campaigns, and, most importantly, encapsulates the lived reality of millions seeking work. To understand the unemployment rate is to understand a core tension within capitalist economies—the balance between labor supply and demand, growth and contraction, opportunity and stagnation. This article will dissect this crucial metric, moving beyond the headline number to explore its calculation, its various forms, its global context, and its profound implications for society at large. We will delve into what the unemployment rate reveals, what it obscures, and why it remains an indispensable, if imperfect, tool for policymakers, investors, and citizens alike.

Deconstructing the Headline Number: How the Unemployment Rate is Calculated

The process of calculating the official unemployment rate is a massive statistical undertaking, often misunderstood by the public. It does not simply count the number of people receiving unemployment benefits. Instead, it relies on large-scale surveys, such as the Current Population Survey (CPS) in the United States, which contacts tens of thousands of households monthly. The foundational concept revolves around dividing the civilian labor force into three groups: the employed, the unemployed, and those not in the labor force. An individual is classified as employed if they did any work for pay or profit during the survey week. The unemployed are those who were not employed but were available for work and had actively sought employment in the prior four weeks. The crucial formula, then, is the number of unemployed people divided by the total civilian labor force (which is the sum of the employed and unemployed), multiplied by one hundred to create a percentage. This calculation seems straightforward, but its devilish complexity lies in the precise definitions of “active job search” and “availability,” which can exclude many who want work but have become discouraged, and so on.

Furthermore, the institutional framework supporting this data collection is vast. Statistical agencies employ rigorous methodologies to ensure sample representativeness, adjust for seasonal variations (like holiday hiring or summer job losses for teachers), and revise preliminary estimates. The result is a seasonally adjusted monthly figure that economists and journalists treat as a key barometer of economic performance. However, this official rate, often called U-3, is just the tip of the iceberg. It provides a standardized, consistent measure for comparison over time, but it is intentionally narrow. It does not capture everyone experiencing labor market distress, a reality that has led to the development of alternative measures that paint a broader, and sometimes more concerning, picture of underutilization in the workforce, which we will explore in subsequent sections.

Beyond U-3: The Spectrum of Labor Underutilization

A critical insight for any expert analyst is that the headline unemployment rate, or U-3, tells only part of the story. To gain a comprehensive view, one must examine the full spectrum of labor underutilization measures. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, for instance, publishes six alternative measures (U-1 through U-6), each with a progressively broader definition. U-1 is the most restrictive, counting only those unemployed for 15 weeks or longer. U-2 includes those who lost their jobs or completed temporary work. The headline U-3, as discussed, includes all unemployed who are actively searching. The expansion begins with U-4, which adds “discouraged workers”—those who want a job and are available but have stopped looking because they believe no work is available for them.

The most comprehensive standard measure is U-6, often called the “real unemployment rate.” This rate includes not only all unemployed individuals from U-3 but also adds two significant groups: marginally attached workers (which includes discouraged workers) and those employed part-time for economic reasons. This last group, also known as involuntary part-time workers, are people working less than 35 hours per week because their hours were cut back or because they cannot find full-time employment. During economic recoveries, the U-6 rate often remains elevated long after U-3 has fallen, indicating a prevalence of underemployment and hidden slack in the labor market. For a true understanding of economic hardship and labor market weakness, examining U-6 alongside U-3 is essential. It reveals the quality, not just the quantity, of job creation and highlights groups that are struggling despite being technically “employed,” and so on.

Frictional, Structural, Cyclical, and Seasonal: The Four Faces of Unemployment

Economists categorize unemployment into four primary types, each with distinct causes and policy implications. Understanding these categories is fundamental to diagnosing economic problems and prescribing correct solutions. Frictional unemployment is the short-term, voluntary unemployment that occurs when workers are between jobs or are new entrants to the labor force (like recent graduates). It is a natural and even healthy feature of a dynamic economy where people move to find better matches for their skills, leading to greater productivity and satisfaction. This type of unemployment will always exist to some degree.

Structural unemployment, however, is more pernicious. It arises from a fundamental mismatch between the skills employers need and the skills the workforce possesses, or from a geographic mismatch between job openings and workers. Examples include technological obsolescence, such as the decline of manufacturing jobs due to automation, or the collapse of a dominant local industry. Addressing structural unemployment requires long-term strategies like retraining programs, education reform, and incentives for worker relocation. Cyclical unemployment is directly tied to the business cycle. It increases during economic recessions and contractions when aggregate demand for goods and services falls, leading companies to lay off workers. Conversely, it decreases during economic booms. Monetary and fiscal stimulus are typical tools to combat cyclical unemployment. Finally, seasonal unemployment occurs due to predictable, recurring changes in labor demand based on seasons, weather, or the calendar, such as in agriculture, tourism, or retail. While expected, it can cause significant hardship for workers in affected industries who may not have year-round employment.

| Type of Unemployment | Cause | Duration | Example | Policy Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frictional | Job transitions, new entrants | Short-term | Recent graduate seeking first job | Improving job-matching services (job boards, fairs) |

| Structural | Skill/location mismatch, tech change | Long-term | Coal miner after mine closure; factory worker replaced by robot | Retraining programs, education subsidies, relocation aid |

| Cyclical | Economic downturn (low demand) | Medium-term | Layoffs during a recession | Interest rate cuts, government stimulus spending |

| Seasonal | Predictable seasonal patterns | Periodic | Lifeguard in winter; retail worker after holidays | Unemployment insurance, seeking complementary off-season work |

The Global Perspective: Unemployment Rates Around the World

The unemployment rate is not a uniformly comparable statistic across international borders. Different countries employ varying definitions, methodologies, and cultural contexts for work and job search, making direct comparisons fraught with difficulty. For instance, some nations have large informal economies where people work without official contracts or reporting; these individuals may not show up in official employment surveys. Other countries have different thresholds for what constitutes “active” job search or may include military personnel in their labor force calculations. Therefore, when examining global unemployment data from sources like the International Labour Organization (ILO) or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), it is crucial to consider these methodological differences.

Nevertheless, broad patterns and disparities are evident. Advanced economies often exhibit lower unemployment rates during stable growth periods, though they can suffer sharp spikes during global crises. Within Europe, there are stark contrasts, with nations like Germany and the Netherlands traditionally maintaining low rates, while Southern European countries like Spain and Greece have historically struggled with high youth and overall unemployment, exacerbated by structural rigidities in their labor markets. Emerging economies may report surprisingly low official rates, but this often masks widespread underemployment and vulnerable employment within the informal sector. Furthermore, demographic structures heavily influence these figures; a nation with a very young population may have a high unemployment rate simply because many new entrants are flooding the labor market faster than jobs can be created. Analyzing global unemployment thus requires a nuanced approach that looks beyond the raw numbers to the underlying economic structures, social safety nets, and measurement practices, and so on.

The Human Cost: Social and Psychological Impacts of Joblessness

While economists focus on percentages and trends, the true weight of the unemployment rate is borne on a human scale. The consequences of prolonged joblessness extend far beyond lost income, inflicting deep social and psychological wounds. Research consistently shows that unemployment is strongly linked to declines in mental health, including increased rates of depression, anxiety, and loss of self-esteem. The stress of financial insecurity, the loss of daily structure and social contact provided by work, and the erosion of personal identity can be profoundly damaging. This psychological toll often ripples outward, affecting families and communities.

The social impacts are equally severe. Long-term unemployment can lead to skill atrophy, making it harder for individuals to re-enter the workforce, creating a vicious cycle of discouragement. It is associated with higher rates of substance abuse, domestic strife, and poorer physical health outcomes. On a community level, areas with persistently high unemployment can experience a breakdown of social cohesion, increased crime, and a generational cycle of poverty where a lack of opportunity becomes entrenched. The unemployment rate, therefore, is not merely an economic indicator but a proxy for social well-being. High and persistent unemployment can erode the social fabric, diminish human capital, and create lasting scars on a nation’s potential. Addressing it is not just an economic imperative but a moral one, requiring policies that support both the financial and psychological needs of those out of work.

Policy Toolkit: Government and Central Bank Responses to High Unemployment

Governments and central banks possess a range of tools to combat high unemployment, particularly when it is cyclical in nature. Their responses are typically divided into two main categories: fiscal policy and monetary policy. Fiscal policy involves changes in government taxation and spending. To stimulate job creation during a downturn, a government may engage in expansionary fiscal policy: increasing spending on public works projects (infrastructure), providing direct aid to households (stimulus checks), or offering tax incentives to businesses for hiring and investment. These measures aim to boost aggregate demand, encouraging companies to produce more and, consequently, hire more workers. Conversely, contractionary fiscal policy (raising taxes, cutting spending) can cool an overheating economy but may also increase unemployment.

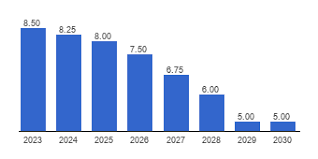

Monetary policy, managed by a nation’s central bank, focuses on influencing interest rates and the money supply. To fight cyclical unemployment, a central bank like the Federal Reserve will typically implement an expansionary or “easy” monetary policy. This involves lowering benchmark interest rates, which makes borrowing cheaper for businesses and consumers. The goal is to stimulate investment, spending, and hiring. In extreme situations, such as after the 2008 financial crisis or during the COVID-19 pandemic, central banks may resort to unconventional tools like quantitative easing—large-scale purchases of financial assets to inject liquidity into the economy. The challenge for policymakers is timing and scale: applying the right medicine in the right dose without triggering high inflation or creating asset bubbles. For structural unemployment, these short-term tools are less effective, necessitating long-term investments in education, training, and workforce development.

“The misery of unemployment is not just in the lack of money, but in the lack of purpose, structure, and the sense of shared endeavor that work provides.” — This reflects a common understanding among sociologists and economists about the multifaceted damage of joblessness.

The Inflation Connection: Navigating the Phillips Curve Dilemma

A central concept in macroeconomic policy is the historical relationship between unemployment and inflation, often illustrated by the Phillips Curve. The traditional short-run Phillips Curve suggests an inverse relationship: when unemployment is low, inflation tends to be high, and vice versa. The logic is that low unemployment means a tight labor market, where businesses must compete for workers by offering higher wages. These increased labor costs are then often passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices, fueling inflation. Conversely, high unemployment implies slack in the labor market, weakening workers’ bargaining power and putting downward pressure on wages and prices.

This relationship poses a profound dilemma for policymakers, particularly central banks tasked with dual mandates of price stability and maximum employment. If the economy is overheating with very low unemployment and rising inflation, the central bank may raise interest rates to cool demand, a move that risks increasing unemployment. If unemployment is high and inflation is low, they may cut rates to stimulate hiring, risking an inflationary spike. However, this trade-off has become less predictable in recent decades. The 1970s experienced “stagflation”—high unemployment and high inflation—breaking the simple Phillips Curve model. In the 2010s, many advanced economies saw low unemployment without a corresponding surge in inflation, flattening the perceived curve. This complexity means modern policymakers must navigate a nuanced landscape, using a wide array of data to judge the true level of labor market slack and inflationary pressures, rather than relying on a simple historical rule of thumb.

Demographic Disparities: How Unemployment Affects Different Groups Unequally

The aggregate unemployment rate masks vast and persistent inequalities among different demographic groups. These disparities reveal how factors like race, age, gender, and education level create uneven experiences within the same economy. Historically, in many countries, the unemployment rate for racial and ethnic minorities is consistently and significantly higher than for the majority population. In the United States, for example, the Black unemployment rate has typically been about twice that of the White unemployment rate, a gap that persists even during periods of strong economic growth. This points to deep-seated structural issues, including discrimination in hiring, geographic segregation, disparities in educational quality, and gaps in professional networks.

Age is another major fault line. Youth unemployment (for those aged 15-24) is almost always markedly higher than the overall rate. Young people often lack experience, have less-established networks, and may be seeking entry-level positions in a competitive field. High youth unemployment can lead to “scarring effects,” damaging long-term career prospects and earnings potential. Conversely, older workers who lose jobs may face age discrimination and find retraining difficult, leading to prolonged spells of unemployment or forced early retirement. Gender gaps, while narrowing in many developed nations, still exist, often influenced by occupational segregation, caregiving responsibilities, and part-time work patterns. Analyzing these subgroup rates is essential for crafting targeted, equitable policies that address the specific barriers faced by different communities in the labor market, and so on.

Technological Disruption and the Future of Work: A New Unemployment Paradigm?

The accelerating pace of technological innovation, particularly in automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and robotics, has sparked a vigorous debate about a potential new paradigm for unemployment. The fear is that of technological unemployment—a scenario where machines permanently displace human workers on a massive scale, not just in manual tasks but increasingly in cognitive and service roles. From self-checkout kiosks and automated warehouses to AI-powered diagnostic tools and algorithmic trading, technology is reshaping the demand for labor. This creates a potent form of structural unemployment, where the skills of displaced workers may become obsolete faster than they can be retrained.

However, the historical record offers a counterpoint. Past technological revolutions, from the loom to the personal computer, ultimately created more jobs than they destroyed, albeit after painful periods of transition. They generated entirely new industries and professions that were previously unimaginable. The critical question for the 21st century is whether AI and robotics represent a difference in kind, not just degree. Experts are divided. Some foresee a future with a significant “useless class” of unemployable people, while others believe new, uniquely human-centric roles will emerge in care, creativity, and complex problem-solving. The policy challenge is monumental: it necessitates a fundamental rethinking of education systems to emphasize adaptability and lifelong learning, stronger social safety nets (like concepts of universal basic income), and perhaps new definitions of work itself. The future unemployment rate may increasingly measure not just a lack of jobs, but a mismatch between human potential and a rapidly evolving economic system.

The Ripple Effects: How Unemployment Influences Markets and Investment

The unemployment rate is a key driver of financial market sentiment and investment decisions worldwide. For equity (stock) markets, the relationship is complex and often interpreted through the lens of future corporate profits and central bank policy. A falling unemployment rate in a healthy economy suggests strong consumer demand, which can boost corporate revenues and earnings, lifting stock prices. However, if the rate falls too low, investors may fear that it will trigger wage inflation, squeeze corporate profit margins, and provoke the central bank into raising interest rates—a move that typically makes stocks less attractive relative to bonds. Therefore, markets sometimes react negatively to “too good” employment news.

For bond markets, the reaction is more direct. High unemployment suggests economic weakness, low inflation, and a potential for central bank stimulus (lower rates), which makes existing bonds with higher fixed coupons more valuable, pushing bond prices up. Low unemployment signals potential inflation and rate hikes, which pushes bond prices down. The unemployment report is thus a monthly event that can cause significant volatility across all asset classes. For currency markets, a strong labor market and the prospect of higher interest rates can strengthen a nation’s currency, as it attracts foreign capital seeking higher returns. For individual investors and corporate planners, the trend in unemployment serves as a crucial input for forecasting economic growth, consumer spending patterns, and sector-specific opportunities, making it an indispensable piece of the financial puzzle.

Critiques and Limitations: What the Unemployment Rate Doesn’t Tell Us

For all its importance, the official unemployment rate is subject to significant and well-founded critiques. Its primary limitation is its narrow definition, which excludes several large groups of people in precarious labor situations. As discussed, discouraged workers who have given up searching are not counted. The underemployed—those working part-time who desire full-time work or those overqualified for their current roles—are invisible in the U-3 rate. Nor does it account for the quality of employment: it does not distinguish between a high-paying, secure job with benefits and a low-wage, unstable “gig” job. Both are counted equally as “employed.” https://data.oecd.org/unemp/unemployment-rate.htm

Furthermore, the rate says nothing about wage growth, labor force participation, or demographic composition. A falling unemployment rate could be misleading if it is driven by discouraged workers leaving the labor force altogether, rather than by people finding jobs. This is why economists always pair the unemployment rate with the Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR). Additionally, the aggregate national rate obscures severe regional, state, and local disparities. A country may have a 4% national rate but contain regions suffering from depression-level unemployment of 10% or more. Finally, the rate is a lagging indicator, meaning it changes after the economic conditions that caused it have already shifted. Businesses adjust hours and wages before they resort to layoffs, and they are often slow to rehire even after demand recovers. Therefore, while invaluable, the unemployment rate must be analyzed in concert with a dashboard of other indicators for a complete picture of labor market health.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the unemployment rate is a deceptively simple statistic that unlocks a complex world of economic dynamics, human experience, and policy challenges. It serves as an essential compass for navigating the economic landscape, but it is a compass that must be read with a critical and informed eye. From its meticulous calculation to its varied forms—frictional, structural, cyclical, and seasonal—the rate tells a story of market forces, technological change, and social inequality. Its movements influence the highest levels of monetary policy and the most personal levels of individual well-being. While it has undeniable limitations and must be interpreted alongside other data, its power to summarize a nation’s economic struggle and opportunity remains unrivaled. As we move into an era shaped by AI, demographic shifts, and global interconnectedness, understanding the nuances of the unemployment rate will be more crucial than ever for building resilient economies and equitable societies.

FAQs

What is the difference between the unemployment rate and the employment rate?

The unemployment rate is the percentage of the labor force that is jobless and actively seeking work. The employment rate (or employment-to-population ratio) is the percentage of the total working-age population that is employed. The latter accounts for people who have dropped out of the labor force entirely.

Why does the unemployment rate sometimes go up when the economy is improving?

This can happen during the early stages of a recovery. As economic prospects brighten, “discouraged workers” who had stopped looking for jobs may re-enter the labor force and start actively searching again. Since they are now counted as part of the unemployed labor force, the rate can tick up even as jobs are being created—a sign of renewed optimism.